-

1.Relations and Functions

11-

Revision – Functions and its Types 38 minLecture1.1

-

Revision – Functions Types 17 minLecture1.2

-

Revision – Sum Related to Relations 04 minLecture1.3

-

Revision – Sums Related to Relations, Domain and Range 22 minLecture1.4

-

Cartesian Product of Sets, Relation, Domain, Range, Inverse of Relation, Types of Relations 34 minLecture1.5

-

Functions, Intervals 39 minLecture1.6

-

Domain 01 minLecture1.7

-

Problem Based on finding Domain and Range 39 minLecture1.8

-

Types of Real function 31 minLecture1.9

-

Odd & Even Function, Composition of Function 32 minLecture1.10

-

Chapter Notes – Relations and FunctionsLecture1.11

-

-

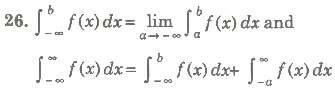

2.Inverse Trigonometric Functions

16-

Revision – Introduction, Some Identities and Some Sums 16 minLecture2.1

-

Revision – Some Sums Related to Trigonometry Identities, trigonometry Functions Table and Its Quadrants 35 minLecture2.2

-

Revision – Trigonometrical Identities-Some important relations and Its related Sums 16 minLecture2.3

-

Revision – Sums Related to Trigonometrical Identities 18 minLecture2.4

-

Revision – Some Trigonometric Identities and its related Sums 42 minLecture2.5

-

Revision – Trigonometry Equations 44 minLecture2.6

-

Revision – Sum Based on Trigonometry Equations 08 minLecture2.7

-

Introduction to Inverse Trigonometry Function, Range, Domain, Question based on Principal Value 37 minLecture2.8

-

Property -1 of Inverse trigo function 28 minLecture2.9

-

Property -2 to 4 of Inverse trigo function 48 minLecture2.10

-

Questions based on properties of Inverse trigo function 19 minLecture2.11

-

Question based on useful substitution 27 minLecture2.12

-

Numerical problems 19 minLecture2.13

-

Numerical problems 24 minLecture2.14

-

Numerical problems , introduction to Differentiation 44 minLecture2.15

-

Chapter Notes – Inverse Trigonometric FunctionsLecture2.16

-

-

3.Matrices

9-

What is matrix 26 minLecture3.1

-

Types of matrix 28 minLecture3.2

-

Operations of matrices 28 minLecture3.3

-

Multiplication of matrices 29 minLecture3.4

-

Properties of a matrices 44 minLecture3.5

-

Numerical problems 19 minLecture3.6

-

Solution of simultaneous linear equation 28 minLecture3.7

-

Solution of simultaneous / Homogenous linear equation 24 minLecture3.8

-

Chapter Notes – MatricesLecture3.9

-

-

4.Determinants

6-

Introduction of Determinants 23 minLecture4.1

-

Properties of Determinants 29 minLecture4.2

-

Numerical problems 15 minLecture4.3

-

Numerical problems 16 minLecture4.4

-

Applications of Determinants 17 minLecture4.5

-

Chapter Notes – DeterminantsLecture4.6

-

-

5.Continuity

7-

Introduction to continuity 28 minLecture5.1

-

Numerical problems 17 minLecture5.2

-

Numerical problems 22 minLecture5.3

-

Basics of continuity 26 minLecture5.4

-

Numerical problems 17 minLecture5.5

-

Numerical problems 11 minLecture5.6

-

Chapter Notes – Continuity and DifferentiabilityLecture5.7

-

-

6.Differentiation

14-

Introduction to Differentiation 27 minLecture6.1

-

Important formula’s 29 minLecture6.2

-

Numerical problems 29 minLecture6.3

-

Numerical problems 31 minLecture6.4

-

Differentiation by using trigonometric substitution 21 minLecture6.5

-

Differentiation of implicit function 21 minLecture6.6

-

Differentiation of logarthmetic function 31 minLecture6.7

-

Differentiation of log function 25 minLecture6.8

-

Infinite series & parametric function 26 minLecture6.9

-

Infinite series & parametric function 27 minLecture6.10

-

Higher order derivatives 27 minLecture6.11

-

Differentiation of function of a function 16 minLecture6.12

-

Numerical problems 27 minLecture6.13

-

Numerical problems 04 minLecture6.14

-

-

7.Mean Value Theorem

4-

Lagrange theorem 24 minLecture7.1

-

Rolle’s theorem 20 minLecture7.2

-

Lagrange theorem 24 minLecture7.3

-

Rolle’s theorem 20 minLecture7.4

-

-

8.Applications of Derivatives

6-

Rate of change of Quantities 30 minLecture8.1

-

Rate of change of Quantities 18 minLecture8.2

-

Rate of change of Quantities 18 minLecture8.3

-

Approximation 10 minLecture8.4

-

Approximation 05 minLecture8.5

-

Chapter Notes – Applications of DerivativesLecture8.6

-

-

9.Increasing and Decreasing Function

5-

Introduction 36 minLecture9.1

-

Numerical Problem 26 minLecture9.2

-

Numerical Problem 22 minLecture9.3

-

Numerical Problem 22 minLecture9.4

-

Numerical Problem 21 minLecture9.5

-

-

10.Tangents and Normal

3-

Introduction 34 minLecture10.1

-

Numerical Problems 32 minLecture10.2

-

Angle of intersection of two curves 27 minLecture10.3

-

-

11.Maxima and Minima

10-

Introduction 28 minLecture11.1

-

Local maxima & Local Minima 27 minLecture11.2

-

Numerical Problems 37 minLecture11.3

-

Maximum & minimum value in closed interval 19 minLecture11.4

-

Application of Maxima & Minima 10 minLecture11.5

-

Application of Maxima & Minima 14 minLecture11.6

-

Numerical Problems 17 minLecture11.7

-

Numerical Problems 18 minLecture11.8

-

Numerical Problems 15 minLecture11.9

-

Numerical Problems 14 minLecture11.10

-

-

12.Integrations

19-

Introduction to Indefinite Integration 37 minLecture12.1

-

Integration by substitution 25 minLecture12.2

-

Numerical problems on Substitution 39 minLecture12.3

-

Numerical problems on Substitution 04 minLecture12.4

-

Integration various types of particular function (Identities) 31 minLecture12.5

-

Integration by parts-1 18 minLecture12.6

-

Integration by parts-2 10 minLecture12.7

-

Integration by parts-2 16 minLecture12.8

-

Integration by parts-2 08 minLecture12.9

-

ILATE Rule 12 minLecture12.10

-

Integration of some special function 07 minLecture12.11

-

Integration of some special function 06 minLecture12.12

-

Integration by substitution using trigonometric 14 minLecture12.13

-

Evaluation of some specific Integration 12 minLecture12.14

-

Evaluation of some specific Integration 29 minLecture12.15

-

Integration by partial fraction 27 minLecture12.16

-

Integration of some special function 11 minLecture12.17

-

Numerical Problems based on partial fraction 20 minLecture12.18

-

Chapter Notes – IntegralsLecture12.19

-

-

13.Definite Integrals

11-

Introduction 24 minLecture13.1

-

Properties of Definite Integration 19 minLecture13.2

-

Numerical problem based on properties 22 minLecture13.3

-

Area under the curve 16 minLecture13.4

-

Area under the curve (Ellipse) 20 minLecture13.5

-

Area under the curve (Parabola) 10 minLecture13.6

-

Area under the curve (Parabola & Circle) 40 minLecture13.7

-

Area bounded by lines 10 minLecture13.8

-

Numerical problems 25 minLecture13.9

-

Area under the curve (Circle ) 02 minLecture13.10

-

Chapter Notes – Application of IntegralsLecture13.11

-

-

14.Differential Equations

6-

Introduction to chapter 38 minLecture14.1

-

Solution of D.E. – Variable separation methods 14 minLecture14.2

-

Solution of D.E. – Variable separation methods 27 minLecture14.3

-

Solution of D.E. – Second order 21 minLecture14.4

-

Homogeneous D.E. 31 minLecture14.5

-

Chapter Notes – Differential EquationsLecture14.6

-

-

15.Vectors

12-

Introduction , Basic concepts , types of vector 34 minLecture15.1

-

Position vector, distance between two points, section formula 44 minLecture15.2

-

Numerical problem 02 minLecture15.3

-

collinearity of points and coplanarity of vector 34 minLecture15.4

-

Direction cosine 18 minLecture15.5

-

Projection , Dot product, Cauchy- Schwarz inequality 24 minLecture15.6

-

Numerical problem (dot product) 20 minLecture15.7

-

Vector (Cross) product , Lagrange’s Identity 15 minLecture15.8

-

Numerical problem (cross product) 38 minLecture15.9

-

Numerical problem (cross product) 06 minLecture15.10

-

Numerical problem (cross product) 22 minLecture15.11

-

Chapter Notes – VectorsLecture15.12

-

-

16.Three Dimensional Geometry

7-

Introduction to 3D, axis in 3D, plane in 3D, Distance between two points 32 minLecture16.1

-

Numerical problems , section formula , centroid of a triangle 35 minLecture16.2

-

projection , angle between two lines 40 minLecture16.3

-

Numerical Problem based on Direction ratio & cosine 02 minLecture16.4

-

locus of any point 15 minLecture16.5

-

Numerical Problem based on locus 16 minLecture16.6

-

Chapter Notes – Three Dimensional GeometryLecture16.7

-

-

17.Direction Cosine

2-

Introduction 34 minLecture17.1

-

Angle Between two vectors 25 minLecture17.2

-

-

18.Plane

3-

Introduction to plane , general equation of a plane , normal form 31 minLecture18.1

-

Angle between two planes 30 minLecture18.2

-

Distance of a point from a plane 29 minLecture18.3

-

-

19.Straight Lines

22-

Revision – Introduction, Equation of Line, Slope or Gradient of a line 24 minLecture19.1

-

Revision – Sums Related to Finding the Slope, Angle Between two Lines 22 minLecture19.2

-

Revision – Cases for Angle B/w two Lines, Different forms of Line Equation 23 minLecture19.3

-

Revision – Sums Related Finding the Equation of Line 27 minLecture19.4

-

Revision – Sums based on Previous Concepts of Straight line 32 minLecture19.5

-

Revision – Parametric Form of a Straight Line 16 minLecture19.6

-

Revision – Sums Related to Parametric Form of a Straight Line 17 minLecture19.7

-

Revision – Sums Based on Concurrent of lines, Angle b/w Two Lines 45 minLecture19.8

-

Revision – Different condition for Angle b/w two lines 04 minLecture19.9

-

Revision – Sums Based on Angle b/w Two Lines 36 minLecture19.10

-

Revision – Equation of Straight line Passes Through a Point and Make an Angle with Another Line 09 minLecture19.11

-

Revision – Sums Based on Equation of Straight line Passes Through a Point and Make an Angle with Another Line 15 minLecture19.12

-

Revision – Sums Based on Equation of Straight line Passes Through a Point and Make an Angle with Another Line 17 minLecture19.13

-

Revision – Finding the Distance of a point from the line 35 minLecture19.14

-

Revision – Sum Based on Finding the Distance of a point from the line and B/w Two Parallel Lines 33 minLecture19.15

-

Introduction to straight line , symmetric form , Angle between the lines 27 minLecture19.16

-

Numerical Problem 18 minLecture19.17

-

Angle between two lines 32 minLecture19.18

-

Unsymmetric form of Line 26 minLecture19.19

-

Numerical problem , perpendicular distance of a point from a line 22 minLecture19.20

-

Numerical Problem 21 minLecture19.21

-

Numerical problem , Condition for a line lie on a plane 26 minLecture19.22

-

-

20.Straight Lines (Vector)

4-

Vector and Cartesian equation of a straight line 27 minLecture20.1

-

Angle between two straight line 25 minLecture20.2

-

Numerical problems 37 minLecture20.3

-

Shortest Distance between two lines 22 minLecture20.4

-

-

21.Linear Programming

5-

Introduction to L.P. 30 minLecture21.1

-

Numerical Problems 43 minLecture21.2

-

Numerical Problems 23 minLecture21.3

-

Numerical Problems 17 minLecture21.4

-

Chapter Notes – Linear ProgrammingLecture21.5

-

-

22.Probability

23-

Introduction to probability 41 minLecture22.1

-

Types of events 42 minLecture22.2

-

Numerical problems 30 minLecture22.3

-

Conditional probability 12 minLecture22.4

-

Numerical problems 09 minLecture22.5

-

Numerical problems (conditional Probability) 04 minLecture22.6

-

Numerical problems (conditional Probability) 06 minLecture22.7

-

Numerical problems (conditional Probability) 05 minLecture22.8

-

Numerical problems (conditional Probability) 06 minLecture22.9

-

Bayes’ Theorem 17 minLecture22.10

-

Numerical problem ( conditional Probability) 04 minLecture22.11

-

Numerical problem ( Baye’s Theorem) 19 minLecture22.12

-

Numerical problem ( Baye’s Theorem) 18 minLecture22.13

-

Numerical problem ( Baye’s Theorem) 10 minLecture22.14

-

Mean and Variance of a random variable 09 minLecture22.15

-

Mean and Variance of a random variable 09 minLecture22.16

-

Mean and Variance of a random variable 08 minLecture22.17

-

Mean and Variance of a discrete random variable 07 minLecture22.18

-

Numerical problem 18 minLecture22.19

-

Bernoulli’s Trials & Binomial Distribution 11 minLecture22.20

-

Numerical problem 12 minLecture22.21

-

Mean and Variance of Binomial Distribution 05 minLecture22.22

-

Chapter Notes – ProbabilityLecture22.23

-

-

23.Limits

4-

Introduction to limits 35 minLecture23.1

-

Numerical problems 27 minLecture23.2

-

Rationalization 33 minLecture23.3

-

Limits in trigonometry 29 minLecture23.4

-

-

24.Partial Fractions

4-

Introduction to partial fraction 27 minLecture24.1

-

Partial Fractions 02 29 minLecture24.2

-

Partial Fractions 03 17 minLecture24.3

-

Improper partial fraction 20 minLecture24.4

-

Chapter Notes – Application of Integrals

Let f(x) be a function defined on the interval [a, b] and F(x) be its anti-derivative. Then,

![]()

The above is called the second fundamental theorem of calculus.

![]() is defined as the definite integral of f(x) from x = a to x = b. The numbers and b are called limits of integration. We write

is defined as the definite integral of f(x) from x = a to x = b. The numbers and b are called limits of integration. We write

![]()

Evaluation of Definite Integrals by Substitution

Consider a definite integral of the following form

![]()

Step 1 Substitute g(x) = t

⇒ g ‘(x) dx = dt

Step 2 Find the limits of integration in new system of variable i.e.. the lower limit is g(a) and the upper limit is g(b) and the g(b) integral is now![]()

Step 3 Evaluate the integral, so obtained by usual method.

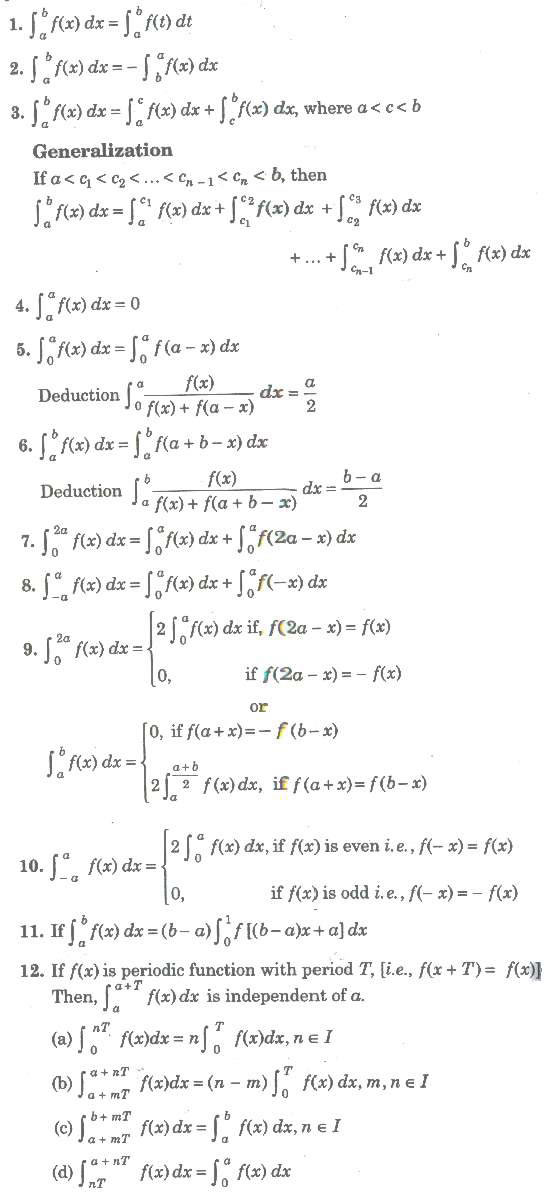

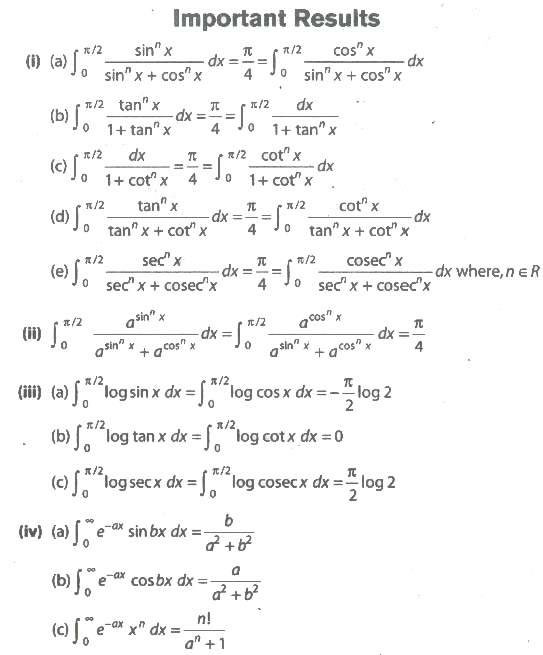

Properties of Definite Integral

13. Leibnitz Rule for Differentiation Under Integral Sign

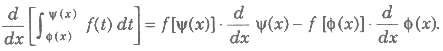

(a) If Φ(x) and ψ(x) are defined on [a, b] and differentiable for every x and f(t) is continuous, then

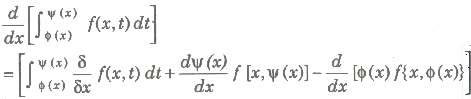

(b) If Φ(x) and ψ(x) are defined on [a, b] and differentiable for every x and f(t) is continuous, then

14. If f(x) ≥ 0 on the interval [a, b], then![]()

15. If (x) ≤ Φ(x) for x ∈ [a, b], then ![]()

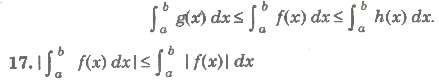

16. If at every point x of an interval [a, b] the inequalities g(x) ≤ f(x) ≤ h(x) are fulfilled, then

18. If m is the least value and M is the greatest value of the function f(x) on the interval [a, bl. (estimation of an integral), then

![]()

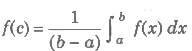

19. If f is continuous on [a, b], then there exists a number c in [a, b] at which

is called the mean value of the function f(x) on the interval [a, b].

20. If f22 (x) and g2 (x) are integrable on [a, b], then

![]()

21. Let a function f(x, α) be continuous for a ≤ x ≤ b and c ≤ α ≤ d.

Then, for any α ∈ [c, d], if

![]()

22. If f(t) is an odd function, then![]() is an even function.

is an even function.

23. If f(t) is an even function, then![]() is an odd function.

is an odd function.

24. If f(t) is an even function, then for non-zero a,![]() is not necessarily an odd function. It will be an odd function, if

is not necessarily an odd function. It will be an odd function, if

![]()

25. If f(x) is continuous on [a, α], then![]() is called an improper integral and is defined as

is called an improper integral and is defined as![]()

27. Geometrically, for f(x) > 0, the improper integral![]() gives area of the figure bounded by the curve y = f(x), the axis and the straight line x = a.

gives area of the figure bounded by the curve y = f(x), the axis and the straight line x = a.

Integral Function

Let f(x) be a continuous function defined on [a, b], then a function φ(x) defined by![]() is called the integral function of the function f.

is called the integral function of the function f.

Properties of Integral Function

1. The integral function of an integrable function is continuous.

2. If φ(x) is the integral function of continuous function, then φ(x) is derivable and of φ ‘ = f(x) for all x ∈ [a, b].

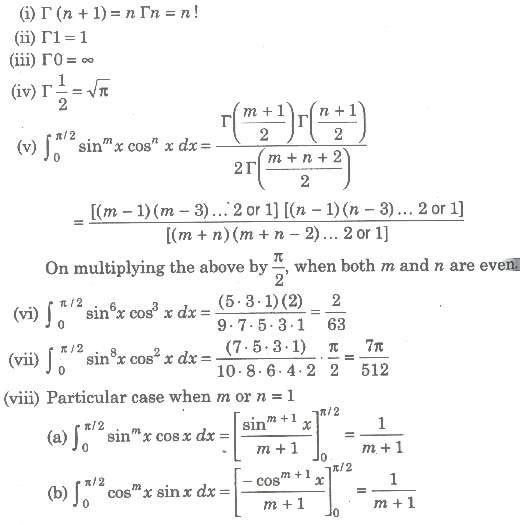

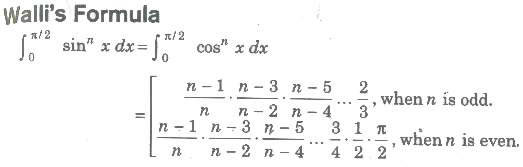

Gamma Function

If n is a positive rational number, then the improper integral![]() is defined as a gamma function and it is denoted by Γn

is defined as a gamma function and it is denoted by Γn

![]()

Properties of Gamma Function

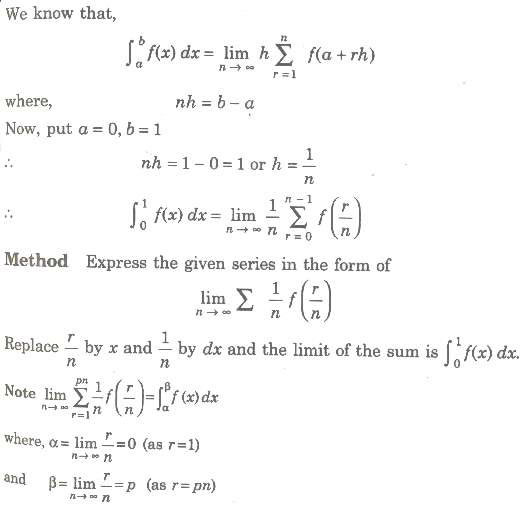

Summation of Series by Definite Integral

The method to evaluate the integral, as limit of the sum of an infinite series is known as integration by first principle.

Area of Bounded Region

The space occupied by the curve along with the axis, under the given condition is called area of bounded region.

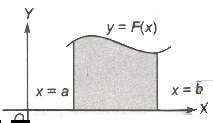

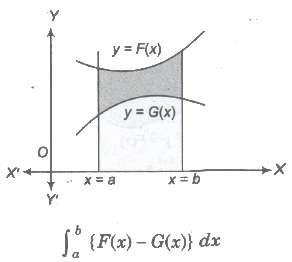

(i) The area bounded by the curve y = F(x) above the X-axis and between the lines x = a, x = b is given by ![]()

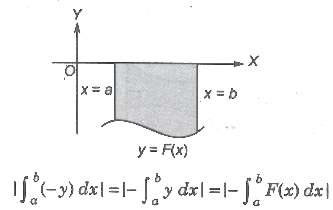

(ii) If the curve between the lines x = a, x = b lies below the X-axis, then the required area is given by

(iii) The area bounded by the curve x = F(y) right to the Y-axis and the lines y = c, y = d is given by

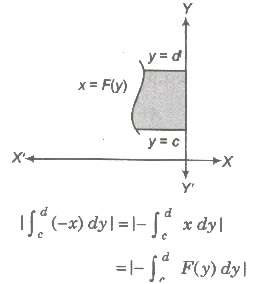

(iv) If the curve between the lines y = c, y = d left to the Y-axis, then the area is given by

(v) Area bounded by two curves y = F (x) and y = G (x) between x = a and x = b is given by

(vi) Area bounded by two curves x = f(y) and x = g(y) between y=c and y=d is given by![]()

(vii) If F (x) ≥. G (x) in [a, c] and F (x) ≤ G (x) in [c,d], where a < c < b, then area of the region bounded by the curves is given as

![]()

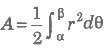

Area of Curves Given by Polar Equations

Let f(θ) be a continuous function, θ ∈ (a, α), then the are t bounded by the curve r = f(θ) and <β) is

Area of Parametric Curves

Let x = φ(t) and y = ψ(t) be two parametric curves, then area bounded by the curve, X-axis and ordinates x = φ(t1), x = ψ(t2) is

![]()

Volume and Surface Area

If We revolve any plane curve along any line, then solid so generated is called solid of revolution.

1. Volume of Solid Revolution

1. The volume of the solid generated by revolution of the area bounded by the curve y = f(x), the axis of x and the ordinates![]() it being given that f(x) is a continuous a function in the interval (a, b).

it being given that f(x) is a continuous a function in the interval (a, b).

2. The volume of the solid generated by revolution of the area bounded by the curve x = g(y), the axis of y and two abscissas y = c and y = d is![]() it being given that g(y) is a continuous function in the interval (c, d).

it being given that g(y) is a continuous function in the interval (c, d).

Surface of Solid Revolution

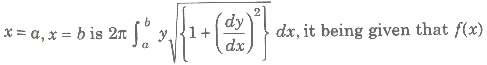

(i) The surface of the solid generated by revolution of the area bounded by the curve y = f(x), the axis of x and the ordinates is a continuous function in the interval (a, b).

is a continuous function in the interval (a, b).

(ii) The surface of the solid generated by revolution of the area bounded by the curve x = f (y), the axis of y and y = c, y = d is![]() continuous function in the interval (c, d).

continuous function in the interval (c, d).

Curve Sketching

1. symmetry

1. If powers of y in a equation of curve are all even, then curve is symmetrical about Xaxis.

2. If powers of x in a equation of curve are all even, then curve is symmetrical about Yaxis.

3. When x is replaced by -x and y is replaced by -y, then curve is symmetrical in opposite quadrant.

4. If x and y are interchanged and equation of curve remains unchanged curve is symmetrical about line y = x.

2. Nature of Origin

1. If point (0, 0) satisfies the equation, then curve passes through origin.

2. If curve passes through origin, then equate low st degree term to zero and get equation of tangent. If there are two tangents, then origin is a double point.

3. Point of Intersection with Axes

1. Put y = 0 and get intersection with X-axis, put x = 0 and get intersection with Y-axis.

2. Now, find equation of tangent at this point i. e. , shift origin to the point of intersection and equate the lowest degree term to zero.

3. Find regions where curve does not exists. i. e., curve will not exit for those values of variable when makes the other imaginary or not defined.

4. Asymptotes

1. Equate coefficient of highest power of x and get asymptote parallel to X-axis.

2. Similarly equate coefficient of highest power of y and get asymptote parallel to Y-axis.

5. The Sign of (dy/dx)

Find points at which (dy/dx) vanishes or becomes infinite. It gives us the points where tngent is parallel or perpendicular to the X-axis.

6. Points of Inflexion

![]() and solve the resulting equation.If some point of inflexion is there, then locate it exactly.

and solve the resulting equation.If some point of inflexion is there, then locate it exactly.

Taking in consideration of all above information, we draw an approximate shape of the curve

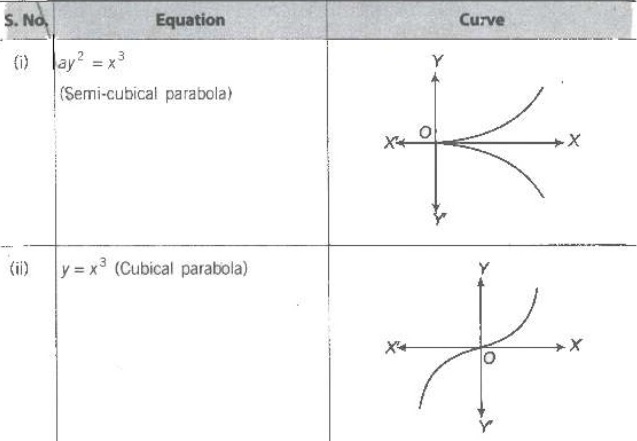

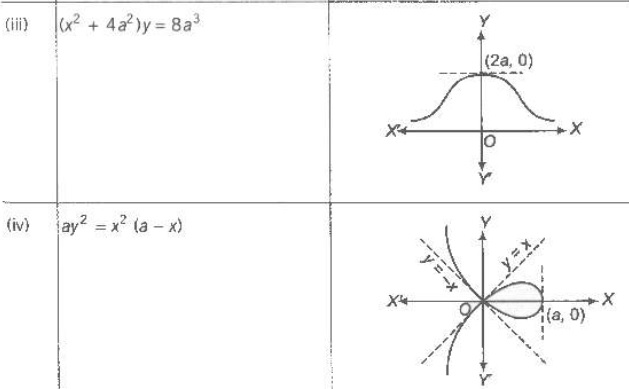

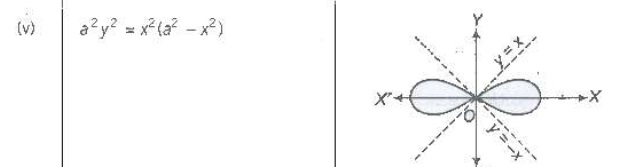

Shape of Some Curves is Given Below